An 18th

Century Historical Detail of Rings

by

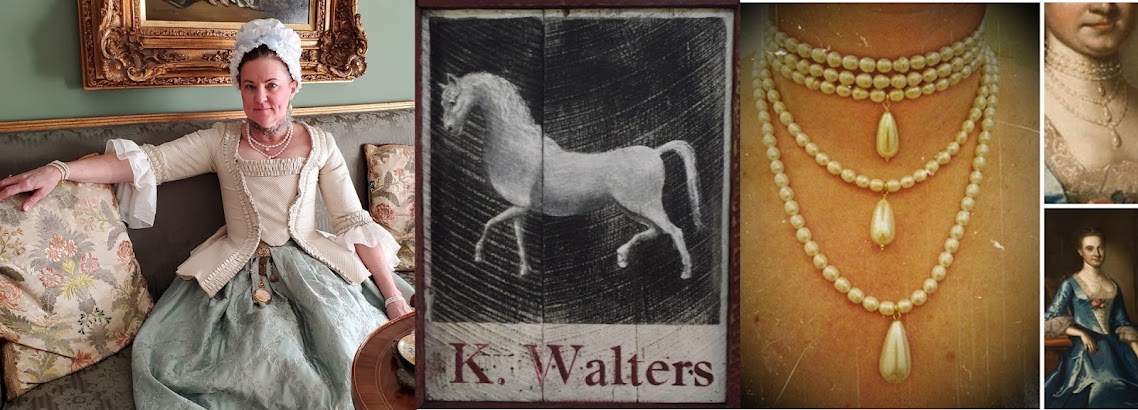

Kimberly K. Walters of

K. Walters at the Sign of the Gray Horse

“This gem is pledge and image of my heart:

A heart that looks and loves, though not

in view.

The jewel has no clearer, purer part –

It may be harder, but is not more

true."

~Mary,

Queen of Scots to Queen Elizabeth

I like to focus on the details of historic

portraits and prints to see what the artist painted. I like to ponder whether these details are

something that the sitter was actually wearing or an artist's rendition. In many cases, we will never know whether what

was painted was really there, but the detail is amazing and often represents what

was commonly worn in the era during which it was painted.

Studying such portraits gives me ideas

about what to offer my customers, as well as what to wear during my own living

history events. Some of us may have

inherited a lovely piece of jewelry or have something already in our possession

that we can use at reenactments. I do

offer many items that can augment those items as new pieces for you to cherish.

In The

History and Poetry of Finger-Rings by Charles Edwards, dated 1880, he says

that “the ring was generally the emblem of fidelity in civil engagements; and

hence, no doubt, its ancient use and functions and distinctions.” It seems that, throughout the ages, rings meant different things when worn on a certain finger

or as given to the intended. Edwards tries

to incorporate into one book what rings meant from the ancients to what he says

is “modern times.”

His book also

goes into some detail about how rings can be connected with power, have supposed

charms and virtues, can be linked to degradation and slavery or used for sad

and wicked purposes. They can even, Edwards maintains, be coupled with

remarkable historical characters or circumstances, and connote love, affection, friendship

(Gimmal or Gimmow Ring) or superstition. He goes on to relate stories about how

rings worn in different cultures or worn by saints are supposed to cure certain

ailments.

Gimmal

or Fede Ring

(Courtesy

of The Jewellery Editor – on-line)

What I like about Edwards' work is that it

is heavily sourced, and he will state whether something is true or suspect. I like the stories, as well, even if they are

not based upon fact. The sentiments are

nice. We are truly appreciative that he

took the time to write this work.

Rings were (and still are) made from many

materials. They were a very popular item

and a bestseller even today. These

included, in the early days, bronze, iron, copper, jet, porcelain, tin, and

even cut steel, to name a few. Popular

materials in the 17th and 18th Centuries were gold and

silver, pinchbeck (or faux gold), and as the old century closed and the new

began, plating and finishing in an antique style (or dead gold) was introduced. Gold or faux gold in rings was generally worn

during this time, but there are instances of silver and a combination of gold

and silver, as well.

I doubt that these were the only materials

they used, and further study of inventories, probate records, and purchase

orders would need to be done. Applications

of enamel are seen, as well, on rings.

We also see rings set with gemstones (sometimes gold or silver foil on

the back), semi-precious stones, or paste (which may also be foiled with a

black dot in the center to emulate a certain cut of diamond). Sometimes they

feature clusters of stones-and shapes created to great effect, as in the Giardinetti flower basket style, Fede (also meaning Faith, with an Urn, Heart, and

Hand) rings, or even rings that looked like belts. In addition, cameos (made of

a multitude of materials) and intaglios were seen, rings fit into rings (or

twist rings, heart and hand rings) ... and I could go on.

Giardinetti Flower Basket gold ring

(Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum)

So Edwards then says something really cool: “An

English work, of but little note, professes to make out 'Love's Telegraph,' as

understood in America; thus, if a gentleman wants [a] wife, he wears [a] ring

on the first finger of the left hand; if he is engaged, he wears it on the

second finger; if married, on the third; and on the fourth if he never intends

to be married. When [a] lady is not engaged, she wears [a] hoop or diamond on

her first finger; if engaged, on the second; if married, on the third; and on

the fourth, if she intends to die maid.”

Threading Pearls, detail from A Portrait of a Woman, by Johann Ulrich Schellenberg, 1745

When I look at portraits and prints, I see

a variety of ways that the rings were worn and no real proof that wearing rings

on certain fingers meant anything.

During the mid-19th century we start to see the custom pertaining to

engagement and wedding rings becoming more prominent. In the 18th Century, posey rings

were exchanged with lines of poetry engraved inside. There were also “keeper rings” that were worn

on the inside and outside of a wedding ring to ensure that it would not be

lost. The heart was supposedly the most

popular motif and was recreated singly, crowned, pierced by arrows, aflame,

tied with a lover’s knot, or had a diamond key attached.

The

Suitor Accepted, by Jean Frederic Schall, 1788

(Courtesy

of Rings Jewelry of Power, Love and Loyalty, by Diana Scarisbrick)

Edwards goes on about another really neat

feature: “Many of our readers are aware that there are name rings, in which the

first letter attaching to each jewel employed will mark a loved one's name or sentiment. In the formation of English rings of this

kind, the terms 'Regard' and 'Dearest' are common. Thus illustrated, R(uby)

E(merald) G(arnet) A(methyst) R(uby) D(iamond) [or] D(iamond) E(merald) A(methyst) R(uby) E(merald)

S(apphire) T(opaz). It is believed that this pretty notion originated (as many

pretty notions do) with the French. The words which the latter generally play

with, in combination of gems, are 'Souvenir' and 'Amitie'…” The book also describes the stones that are

associated with the letters of the alphabet.

I did not include them here, as it would make this article quite long.

REGARD

ring, pinchbeck with colored paste settings

(Courtesy

of Kimberly Walters)

Another history of how birthstones came

about is in Edwards' book. “The Poles have fanciful belief that each month of

the year is under the influence of [a] precious stone, which influence has

corresponding effect on the destiny of [a] person born during the respective

month," he writes. "Consequently, it is customary among friends and

lovers, on birth-days, to make reciprocal presents of trinkets ornamented with

the natal stones." The stones and their influences, corresponding with

each month, are supposed to be as follows: January, Garnet = Constancy and

Fidelity; February, Amethyst = Sincerity; March, Bloodstone = Courage, presence

of mind; April, Diamond = Innocence; May, Emerald = Success in love; June,

Agate = Health and long life; July,

Cornelian = Contented mind; August, Sardonyx = Conjugal Felicity; September,

Chrysolite = Antidote against madness; October, Opal = Hope; November, Topaz =

Fidelity; December, Turquoise = Prosperity.

Georgian

(c. 1800) rock crystal ring, provenance southeastern America. The

stone is a true rock crystal (a type of quartz, like citrine or amethyst), with

a curved surface and a simply faceted back. It is tightly bezel set and the

yellow gold engraved setting is open backed. (Courtesy Laurel Scott)

Then there was the language of flowers,

where Mistletoe was for kisses and fertility, Daisies for purity and innocence,

and bouquets of flowers stood for the virtues of married life. The stones were also combined for double

symbolism.

As to superstitions, it is mentioned that

“In Berkshire, England, there is popular superstition that [a] ring made from

piece of silver collected at the Communion is cure for convulsions and fits of

every kind.”

Edwards then addresses the matter of

"hair" rings. “One of the prettiest rings, used as remembrance, has a

socket for hair and closing shutter," he writes, explaining, "It held

the hair of a loved one, either alive or passed.” I have seen these woven into scenes, braided,

swirled, and surrounded with gemstones, pearls, or in just a plain ring. I have also seen a portrait of the person on

the front with his or her hair in the “socket” in the back. In much of my research, these are called "memento

mori," which has two meanings. The first is that it remembers a loved one;

in the second, it reminds you of your mortality.

Remembrance

Ring with purple garnets surround, hair woven into a tree, and white enameling

on the sides meant to represent a child or virgin

(Courtesy

Kimberly Walters)

During the

Federalist period, rings became thicker with ornamental surfaces. The signet ring was also appropriated by

societies and schools to make emblematic rings.

This may have been the beginning of the class ring for colleges and high

schools.

When searching through portraits of men,

many have their hands hidden in their waistcoats or have gloves on, so it is

difficult to know whether they were wearing rings. I did find a few as of this writing that show

rings, and they are wearing them on their pinkie fingers, their ring fingers,

or both. I am sure there are rings

sitting in a museum or private collection that belonged to many others – but it

still does not tell you which fingers they wore them on.

Douglas, 8th Duke of Hamilton, by Jean Preudhomme, 1774

James Farrell Phillips, by Johann Zoffany

John Mortlock of Cambridge and Abington Hall, Great Abington, Cambridgeshire, by John Downman, 1779, Private Collection

Headed Home After Twelfth Night,

The Trustees of the British Museum

The ladies' portraits show a wide variety of

rings on all fingers. Some have them on

both hands and some just on one. You

will note that there are a lot of plain hoops or bands. I did find it interesting to find a ring with

the initial “S” on it from a 1785 portrait.

Miss Mary Edwards, by William Hogarth, 1742, The Frick Collection

Countess Tolstoy, Ivan Petrovich Argunov , 1768

Mrs Richard Skinner, John Singleton Copely, 1772

Lucy Skelton Gilliam or Mrs Robert Gilliam, by John Durand, circa 1780, Dewitt Wallace

Margaret Whaley Hurst and her daughter Frances, 1782

Lady in Chemise Dress with Blue Sash, Tansey Miniature Collection, 1785

Woman in a Miniature Portrait,

by Gaspare Landi Ritratto di Gentildonna

Detail from Queen Charlotte, by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1789

Mother and Child, by Louis Bernard Coclers, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 1794

Charlotte Schiller, by Louise Seidler, ca. 1815

Kitty Packe “nee Hart,” by Sir William Beechey, 1818-1821

Mrs James Andrew, by John Constable, 1818

Countess Emilia Sommariva Seilliere, by Boulanger Charles Boisfremont, 1833

Mme Ingres, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1859

Since I am

interested in reenacting and living history, I like to end on what types of

rings should you wear? Well, it depends upon

your impression. If you are a camp follower,

I would not wear any rings unless it is the beginning of the war. If you must have a ring on, a plain gold or

silver band in place of your modern wedding and engagement rings, if

applicable, would be a good choice.

Otherwise, look at your level in society, the dates of your

interpretation, and then study the shapes you see in portraits and prints or

even on originals. Be very careful that

those originals have not been altered in some way.

Bibliography:

The

History and Poetry of Finger-Rings by

Charles Edwards, dated 1880

Jewelry

in America 1600-1900 by Martha Gandy Fales, Antique

Collector’s Club, 1995

The new ring guards: the rise in popularity of

antique rings with symbolic meaning, The Jewellery Editor, 13 June 2015 (http://www.thejewelleryeditor.com/vintage/new-ring-guards-rise-popularity-antique-rings-symbolic-meaning/

Georgian Jewellery 1714 to 1830 by Ginny Tedington Dawes with Olivia

Collings, Antique Collector’s Club, 2007

Rings Jewelry of Power, Love and Loyalty, by Diana Scarisbrick, Thames

& Hudson Ltd., London, 2007

Copyright K. Walters at the Sign of the Gray Horse. None of this can be copied or used without the permission of Kimberly K. Walters.

Copyright K. Walters at the Sign of the Gray Horse. None of this can be copied or used without the permission of Kimberly K. Walters.