Since I have recently worked with a manufacturer to have steel hat pins made, I wanted to write about hat pins and their use. I’ve also created a video on how to properly put a hat pin in your hat so that you don’t bend the pin to an unrecognizable state or stab your brains! Please like my channel, like the video, and share!

As usual, I do a quick search on Google Books of the John Ash dictionary Volumes 1 and 2. I did not find a definition of “hat pin” or “hatpin.” I did find definitions of hat and of pin. I also checked Dr. Samuel Johnson’s dictionary of 1752, of which I have a bound copy that I brought back with me from London years ago, and also do not find hat and pin together. This is actually the same for buckles. A good friend of mine reminded me that while these words may not be defined within dictionaries, they may be mentioned and thus identified in orders or advertisements.

The American Hatpin Society (AHS) states that hat pins “ranged in size between 6 and 12 inches long depending on the size of the hat they needed to secure to a woman’s head. They were fancy or practical, made from every available material ranging from precious metals to gemstones to plastics and paste. Hatpin makers marketed their products to the various levels of society, ranging from the extremely ornate and expensive to the simple and functional. The heyday of the hatpin was between the 1880's and 1920’s, after which hair styles became short and the hats became smaller making the pins unnecessary.”

The AHS also includes a small table that shows that as early as the 1400s (15th century), as far back as the Middle Ages in Britain and Europe, pins were used as a device to securely hold the wimples and veils that proper ladies used to cover their hair in place. These small pins and wires were used for hundreds of years. I have also seen 18th and 19th century prints with pins and hair pins laying on the dressing table.

1772, Lewis Walpole Library Digital Collection

By 1800 (19th century) the making of decorative and functional pins was a cottage industry that frequently employed an entire family. They were time consuming to make which resulted in small amounts of pins being available for the demanding public. (AHS)

My note here is that the world had just went through the Revolutionary War by 1800, and imports were not going back and forth for about 10 years or so. Metals would have possibly been melted down for musket balls or hoarded for use with clothing. As Adam Smith mentions below, thousands of pins could be manufactured in a day and would have been available prior to the war and afterwards.

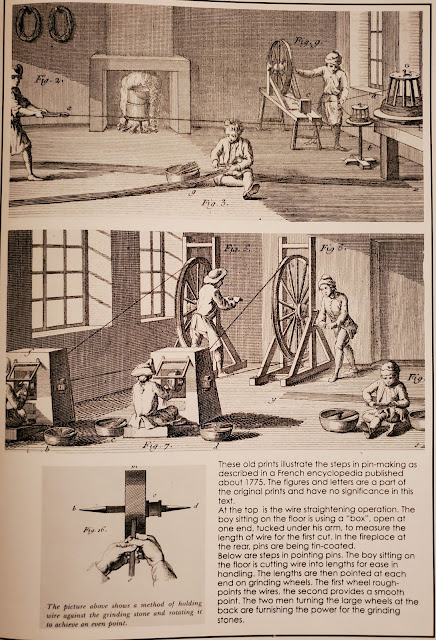

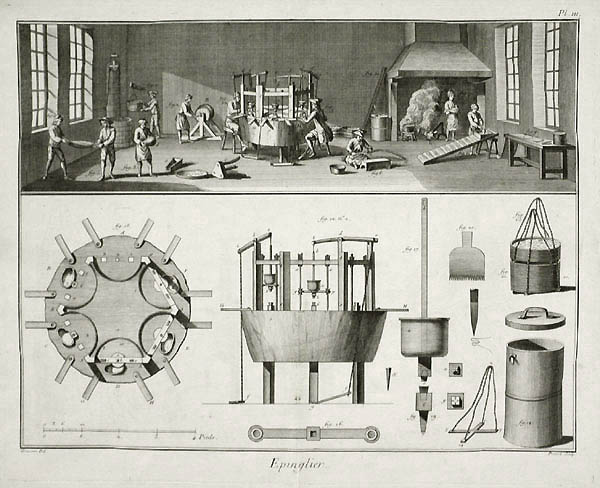

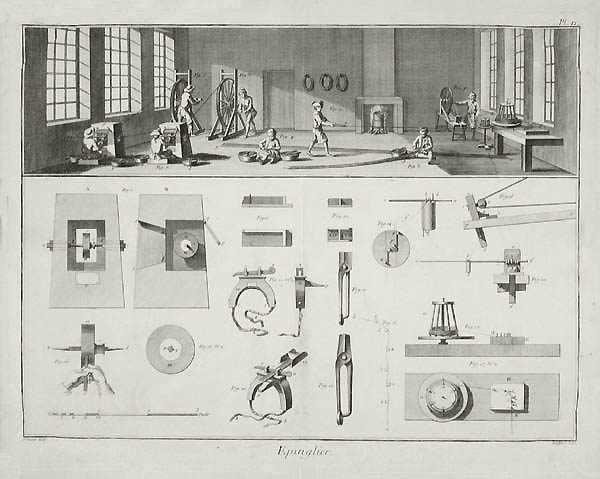

During my research, I found a source titled, “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations” in three volumes by Adam Smith dated 1776 that discusses, among many things about the economies of the world, pin making. While pin makers were a specific guild, the employment of them would have had the same division of labor for the efficiency of making hat and other hair pins and, of course, they would have just been made longer. Smith does describe the knowledge and labor in making them, “…a very trifling manufacture; but one in which the division of labour has been very often taken notice of, the trade of the pin-maker; a workman not educated to this business (which the division of labour has rendered a distinct trade), nor acquainted with the use of the machinery employed in it (to the invention of which the same division of labour has probably given occasion), could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. But in the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades.” I can understand that a person or families making pins at home would not have all of the tools in which to make them in mass quantities in a quick manner.

The manufacture of pins as a trade; however, allowed them to produce so many in a day which is remarkable and described by Smith, “…One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. But though they were very poor, and therefore but indifferently accommodated with the necessary machinery, they could, when they exerted themselves, make among them about twelve pounds of pins in a day. There are in a pound upwards of four thousand pins of a middling size. Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. Each person, therefore, making a tenth part of forty-eight thousand pins, might be considered as making four thousand eight hundred pins in a day…”

Within the Virginia Gazette in 1775, I found mention of someone who knew how to make pins. Also, in a purchase request by William Whetcroft in Annapolis, Maryland, he ordered, “½tt brass joint pin wire…3 gross gilt a pins & wire” (Wallace, Davidson & Johnson Order books).

During the War of 1812, the importation of pins was so expensive that pins began to be manufactured in America, but this industry was not truly successful until about 1836. (Kim’s note here is after the Revolutionary War, America was free from the guilds of England which allowed them to start their own manufactories in a variety of goods.)

Prior to this, pins had to be cut from a length of wire, then sharpened and headed, one by one, by hand as described above by Adam Smith. Within Baker’s Encyclopedia of Hatpins & Hatpin Holders, it is stated that the cost, made them [hatpins] so expensive, it was not uncommon for pins to be presented as gifts to the ladies on birthdays or other occasions of note. When no pins were available, it was perfectly proper to give “pin money,” which was put aside for the time when the pins were available.

In the 1820’s importing hatpins from France was one way of keeping up with demand. Alarmed at the effect the imports had on the balance of trade, in England, Parliament passed an Act restricting the sale of pins to two days a year - January 1st and 2nd. Ladies saved their money all year to be able to spend it on pins in an early example of the "January Sales!" This is thought to be a source of the term "pin money." However, as Queen Victoria taxed her subjects at the beginning of each year to pay for her pins, this could also be the source of the term. (AHS)

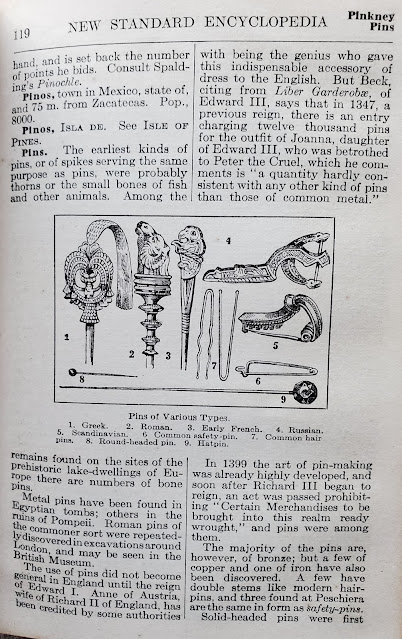

The pin making machine was invented in 1818 and patented by an American, Lemuel Wellman Wright, in 1824 in Great Britain. I found this reference in my copy of Funk & Wagnall’s New Standard Encyclopedia, Volume XX, dated 1931. Also within this volume was a diagram of various pins and a bit of history of pins which included a hatpin in the diagram. According to the Merchants Magazine from 1851, "Lemuel William Wright patented a machine for making solid headed pins both in the United States, and in England." In London, he built "a large stone factory in Lambeth, and constructed some sixty machines, at great expense. It is understood that the machines failed in pointing the pins, and for that reason never could be put into successful operation." The company failed, but one of the investors, D.F. Taylor, created a factory in 1832 in Stroud, Gloucestershire and successfully made pins. (Merchants Magazine, F. Hunt, Vol25, Nov 1851, p641 per Wikipedia)

When the turn of the 20th century came about the rise in the popularity of hatpins, as a result of changing fashions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, saw the Charles Horner jewelry business becoming one of the British market leaders in good quality mass-produced hatpins. Other high quality hatpin makers in the United States were the Unger Bros., the William Link Co., the Paye & Baker Mfg. Co. and Tiffany & Co. (AHS)

It seems that “hat pin” or “hatpin” shows up as a word within the 1975 Britannica Encyclopedia, 15th edition, and says, “hatpin, a long ornamental pin used for fastening a woman’s hat to her hair. In the late Victorian era and the beginning of the 20th century, the hatpin became a popular and important accessory. They were usually about 8 inches (20 centimeters) long and often worn in pairs. They frequently had ornamented heads.” (Baker)

I have had discussions with people regarding hatpins particularly for the 18th century. Many that I know think that they were NOT embellished with decoration and were more utilitarian. I disagree with that premise only because everything else was “decorated” in some way. Paul of Wm Booth Draper fame actually shared a print with me from 1789 that showed hatpins sticking up from a hat – and they are decorated. So, when looking at portraits and prints, be on the lookout for more of this evidence and share it with me!

My steel hatpins are an exclusive to the Sign of the Gray Horse. These are my design and made for my shop. They measure 7-1/2 inches long (19 centimeters) by 1mm thick and are a 15-16 gauge steel. They are also being sold by select sutlers and museum shops since they are so awesome and unique.

My pin has a nice sharp end which should be able to go right through a straw or thick felt hat. The trick is to hold it at the very end of the pin to twist it into the hat and then push it through to avoid bending it to all heck. I won't say that these can't be bent, but they are a really nice strong steel hatpin that should last a long time if cared for properly. They are very similar to the antique Victorian gauge pins which this one is modeled from to get the thickness.

I also sell a higher gauge hatpin in gold or silver plate that I hand embellish with beads and other unique decorations. Remember, the lower the gauge the stronger the pin.

Bibliography -

American Hatpin Society (http://www.americanhatpinsociety.com/tour/history.html)

Ash, John. The New And Complete Dictionary Of The English Language: In Which All The Words are Introduced ... : To Which Is Prefixed, A Comprehensive Grammar ; In Two Volumes. United Kingdom: Dilly, 1775 found on Google Books.

Baker’s Encyclopedia of Hatpins & Hatpin Holders, by Lillian Baker, Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., Atglen, Pennsylvania, 1998.

Johnson, Samuel, LL.D., A Dictionary of the English Language…, 1756

Merchants Magazine, F. Hunt, Vol25, Nov 1851, p641 per Wikipedia

Smith, Adam, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in Three Volumes, 1776. (https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Wealth_of_Nations/Book_I/Chapter_1)

Virginia Gazette, Rockefeller Library Collection On-Line (https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/)

William Whetcroft order from Wallace, Davidson & Johnson from the Maryland State Archives, Chancery Court (Chancery Papers, Exhibits) Wallace, Davidson Johnson, Order Books, 1771/4/25-1775/11/16. MSA S 528-27/28) 14 November 1772 (https://withwallacedavidsonjohnson.blogspot.com/2012/03/supplying-local-jeweler-in-late.html)