Review:

Tea in 18th Century

America

Kimberly K. Walters

By Lynn Price

Assistant Research

Professor, University of Virginia

Assistant Editor, The

Washington Papers

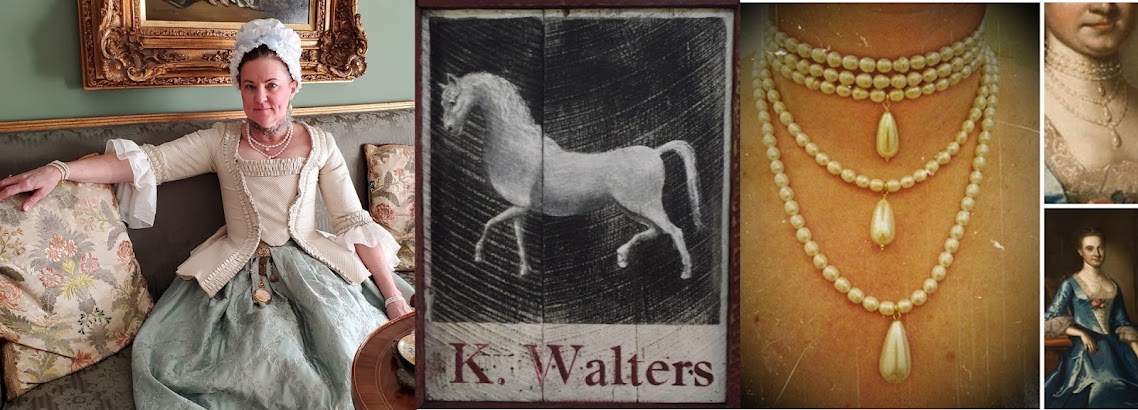

Kimberly

K. Walters is well known and respected in the living history community for her

myriad roles and contributions. As the owner of the Sign of the Gray Horse,

Walters designs and reproduces historically inspired jewelry—with all proceeds

going to rescued horses—that has been used in television shows and

documentaries, on book covers, and at events throughout the United States and

abroad. She is also a prolific living historian, belonging to several military

reenactment units, portraying various personas at historic sites, and teaching

and demonstrating her skills as a master cook with authentic recipes. Walters'

first book, A Book of Cookery, by a Lady, is an extension of her expertise in 18th

century open hearth cooking. Her newest work, Tea in 18th Century America,

highlights her research as an historian focusing on colonial America and the

early republic through the lens of tea and its social, cultural, economical, and

political impact on the new nation.

Tea in

18th Century America begins with the history of tea in England and its arrival

in North America, tracing its ebbs and flows in popularity and the cultural

meaning attached to its use. The book then brings tea alive for the modern

reader, offering recipes of meals to take with tea and desserts, and even a

chapter on historical measurements to assist with recreating such recipes—for

those of us who may not be entirely familiar with the size that corresponds

with "As Thin as a Shilling"! Tea concludes with a biographical

chapter on Margaret Tilghman Carroll, to whom the book is dedicated, and her

life through recipes. Readers will find an extensive variety of primary sources

consulted and quoted, including newspaper advertisements, poems espousing the

virtues of tea, correspondence, diaries, financial accounts, legal acts, and

paintings that together create a vivid narrative.

Tea in

18th Century America offers insights that span a wide range of topics and

interests. Walters' examination of pre-revolutionary America and the power of

tea as a symbol of tyranny or patriotism sheds light on the creation of an

American identity. Her clear explanations of legal acts and taxes on

commodities set the stage for Americans' outrage over the monopoly held by the

East India Tea Company and the beverages' drop in popularity as revolutionary

sentiments grew. To drink tea became a political act. Walters also includes the

important aspect of material culture that is vital to understanding tea as a

commodity. Enjoying tea required tea sets, teapots, spoons, tea chests, and

various other accoutrements, markers of class and financial status. Taking tea,

Walters illustrates, was often a performative act in social settings, with

rules to be followed and customs to learn. Tea was so much more than a

delightful hot beverage.

Novices to

the world of tea need not hesitate to approach Tea in 18th Century America.

Nothing is assumed, and practical knowledge included in the work adds to its

educational benefits. A simple list of tea varieties of the 18th century and

definitions of the words associated with tea sends the reader away with

valuable historical knowledge. For example, Walters' writes that in the era,

"a dish of tea was in reality a cup of tea, for the word 'dish' meant a

cup or vessel used for drinking as well as a utensil to hold food at

meals" (65). Once the reader is fully introduced to the world of 18th

century tea, historical recipes ("receipts" in contemporary vernacular)

with detailed instructions invite readers to step back in time and take tea in

a new way for modern Americans. Thankfully, a chapter of cooking terms and

definitions provides additional help for the less culinary inclined of us.

Kimberly

Walters offers a well researched, well written, and enlightening history of tea

in 18th century America in one manageable volume. Tea in 18th Century America's

usefulness to historians, living historians, interpreters, reenactors, and

others in the field is clear, as is its interest to history fans and tea fans

alike. For a beverage that inspired such words as, "And I lift you to my

lip, And, like nectar, thee I sip; Oh! how charming is the bliss Of thy

aromatic kiss!" (20) should never be resigned to the past.